The world of antique gold artifacts is a delicate balance between preservation and presentation. Among the most debated topics in conservation circles is the use of electrolysis to maintain historical patina—a technique that walks the fine line between science and artistry. Unlike traditional cleaning methods that often strip away centuries of character, electrolysis offers a nuanced approach to safeguarding the story etched into each piece.

Patina, that elusive film of age and oxidation, is more than just tarnish—it's a tangible connection to an object's past. For centuries, collectors and conservators grappled with the dilemma of removing corrosion while preserving this vital historical fingerprint. Early methods often involved abrasive techniques that, while effective at revealing shiny surfaces, inadvertently erased valuable clues about an artifact's origin and journey through time.

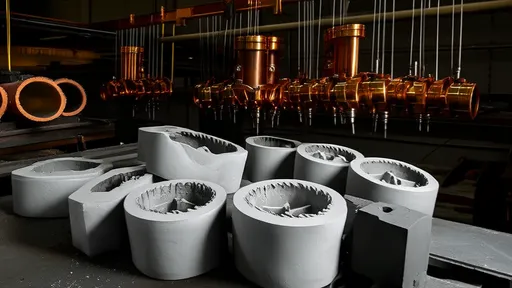

Electrolytic reduction emerged as a game-changer in the late 20th century, particularly for marine-recovered gold objects. The process involves immersing the artifact in a conductive solution and passing a controlled electric current through it. What makes this method revolutionary is its selectivity—it targets corrosive compounds without disturbing stable patina layers that have formed over decades or centuries. This precision allows conservators to stabilize deteriorating artifacts while maintaining their authentic appearance.

The science behind electrolytic patina preservation is fascinatingly complex. Gold, being a noble metal, doesn't corrode in the traditional sense. However, surface accumulations from burial environments or previous restoration attempts often require attention. When properly calibrated, the electrical current causes harmful chlorides and sulfides to migrate away from the metal surface while leaving benign oxides intact. This results in what experts call "differential cleaning"—a process that respects the artifact's biography while addressing active deterioration.

Several high-profile conservation projects have demonstrated electrolysis's potential. The treatment of 18th-century ecclesiastical goldware from Spanish shipwrecks showed remarkable results—salt contamination that threatened to pit surfaces was eliminated, while the soft golden glow acquired through decades of ceremonial use remained undisturbed. Similarly, Etruscan funerary ornaments treated with modified electrolytic techniques retained their characteristic rainbow hues, a phenomenon caused by ancient firing methods that modern goldsmiths still struggle to replicate.

However, the technique isn't without controversy. Some purists argue that any intervention, no matter how subtle, constitutes a break with historical authenticity. They point to instances where overzealous current application resulted in the loss of subtle surface textures that contained valuable information about manufacturing techniques. The conservation community has responded with increasingly refined protocols, including micro-electrolysis setups that allow millimeter-by-millimeter treatment under microscopic observation.

Practical application requires both technical expertise and artistic judgment. Conservators must consider numerous variables: the artifact's alloy composition (as ancient gold rarely appears in pure form), the nature of its corrosion products, and its intended future display environment. A Renaissance pendant might receive completely different treatment than a pre-Columbian nose ornament, even if both show superficially similar greenish deposits. The most successful practitioners combine electrochemical measurements with visual assessment, sometimes spending weeks fine-tuning their approach for a single object.

Recent advancements have made the technology more accessible to smaller institutions. Portable electrolysis units now allow on-site treatment of fragile items that can't be transported. Improved monitoring systems provide real-time data on patina stability during the process. Perhaps most exciting are the digital documentation protocols that create detailed before-and-after records, ensuring that even if minute changes occur, they're thoroughly recorded for future study.

The ethical dimension continues to evolve alongside the technology. Major museums are developing tiered consent systems where stakeholders—from source communities to donor families—can express preferences about patina preservation levels. This recognizes that an object's surface appearance often holds cultural significance beyond its material value. In some cases, electrolysis is being used not to clean, but to stabilize existing patina against future environmental damage.

Looking ahead, researchers are exploring how electrolysis might interact with emerging preservation technologies. Nanoscale protective coatings applied post-treatment could help maintain the stabilized patina for generations. Computational modeling promises to predict how different patina types will respond to various electrochemical scenarios. What remains constant is the principle that guides all such interventions: the understanding that an antique gold object's value lies as much in its history as in its craftsmanship, and that history is often written in the subtle language of its surface.

For collectors and institutions alike, the message is clear. Electrolytic methods, when applied with care and expertise, offer an unprecedented tool for honoring an artifact's complete narrative. They represent not just a technical solution, but a philosophical shift—one that acknowledges preservation doesn't always mean restoration to original brilliance, but sometimes means protecting the beautiful imperfections that time itself has created.

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025

By /Aug 11, 2025